Variety

Rock’s Backpages Celebrates 20 Years of Archiving a Museum of Essential Music Journalism

By Chris Willman

Dec 11, 2021

What do rock 'n' roll and rock journalism have in common? Out of many things, probably, one is that they were both once assumed to be ephemeral. But if the prevalence of classic-rock stations and playlists over the decades has proved that rock 'n' roll really is here to stay, the reporting and criticism surrounding it tended to vanish into thin air, at least in the pre-Internet age (and often since, with so many media companies wantonly messing up or just losing their archives even after making their initial digital transitions).

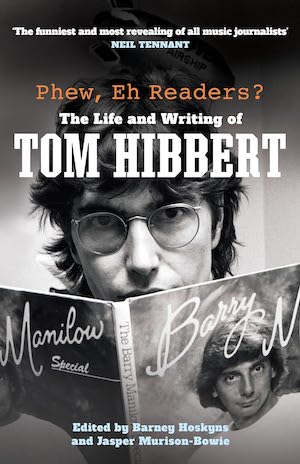

That's where Rock's Backpages comes in — to make sure Lester Bangs and his contemporaries and their work don't survive as just strange, seemingly fictional references in a Cameron Crowe movie. The website has collected tens of thousands of articles about popular music dating back to the mid-'60s and running up to the present day. All that collating didn't happen overnight: The site just celebrated the 20th anniversary of its having been founded by a figure whose byline has its own renown, British journalist Barney Hoskyns, a former staffer for NME and Mojo who's written well-received books about Tom Waits, the Band, glam-rock and the Laurel Canyon scene, even as he's grown Rock's Backpages (found at rocksbackpages.com) into a surprising viable business over the last two decades.

When Hoskyns started the site, Rock's Back Pages was targeted at garden-variety music buffs, but it morphed into more of a research database for libraries, professors, students and documentarians. With individual subscriptions now set at $220 a year, those who don't have a professionally or academically vested interest in taking a deep dive through rock history (and/or deep pockets) will find themselves settling for the free offerings on the front page, which will be plentiful enough for most casual browsers.

Hoskyns spoke with Variety about how the site became self-sustaining and how it came to be an online museum that may well be the best hope rock has of being documented in all its fullness for future generations.

VARIETY: What is the most valuable service that Rock's Backpages provides? There was about three decades of rock journalism before the Internet really took off in the mid-'90s, and now there's been about another quarter-century's worth since. You have so much from before everything started being put online. What's gained by preserving that earlier stuff, especially?

HOSKYNS: We recognize, certainly, that (a certain) era of music journalism or rock criticism is over, really, or at least, music writing of that kind has less importance or significance in the culture. But I think what we've aggregated and archived in a sense transcends the specific history or nature of pop journalism, and actually does provide a kind of parallel social history. We always say to any institutions that are thinking about trialing or subscribing to Rock's Backpages that there is a great deal of social history there — a great deal on fashion and politics and race and religion and celebrity culture… you name it. There's so much that rock 'n' roll and pop have had to say about the world we live in, the attitudes that it embodies, the social changes and shifts. So to be able to get past the kind of consensus or the received ideas of music history, and actually go back and see what musicians and producers and fans and scenesters were actually saying at the time, is important. It's fun and fascinating to be able to refer to that kind of contemporary coverage. Especially in this country, certain magazines sort of just recycle the same stories about the same classic albums and the same tropes, the same events, the same deaths — it's just sort of gotten caught in a kind of echo chamber. And I think it's crucial to be able to circumvent a lot and really go back and see how things were reported at the time, in 1964 and 1972 and 1981 — what were people really saying?

I suspect people will look back on the rock 'n' roll years as a quite circumscribed period — like the baroque period in art, or something. Music will continue, but that sort of 50-year period when it made such a difference to people's lives and was hooked into so much revolutionary change… You know, the power of music to rally the tribes, to rally resistance, to counter the culture — I think probably that's gone. It's been subsumed. Rebellion and revolt have been repackaged as capitalist commodities, and it's very difficult to shock anymore. But it's a period that remains fascinating and certainly worth studying, in terms of the way it parallels the upheaval, the turmoil and turbulence and excitement of the '60s, the decadence of the '70s, and whatever the '80s meant in terms of the way the record companies packaged pop and smoothed it out and dumbed it down. It's a fascinating period that, in probably hundreds of years, people will still be studying and reflecting on.

It's quite an achievement that this has become an institution going on for two decades now. What were your expectations when you started this, and how have you exceeded them?

You've got to remember that I had this idea in 1999, which obviously feels like almost the stone age of the internet. I had no idea, really, or expectation. It was to some degree opportunistic. Everyone was trying to think of things that might work online. All I knew is that I cared passionately about music writing. I'd been a writer at that point for 20 years, and the best music journalism was as important to me in some ways as the music itself. I really believed in what we were doing. I didn't necessarily imagine there could be a way of turning this into a business that paid for itself, because the models were very uncertain at that point. Everyone was trying to figure out if they could make any money at all from the internet.

The idea of subscriptions was sort of there at that point, but then everybody thought that everything should be free. And I'm glad we actually decided to stick to a subscription model the whole way through. We wavered at various moments, but it made more sense to make some money rather than possibly make no money at all. The thinking was that perhaps a few freaks and obsessives and trainspotters will shell out a few pounds every month. We weren't thinking about institutions and group subscriptions at that point. On one level, I wanted to create this archive. On another, maybe we thought we could have some sort of online magazine that people would pay for. It was very wing-and-a-prayer.

And the focus shifted toward being geared more toward academia or researchers or libraries, and away from just wanting to get to your average NME or Rolling Stone reader to pony up a few bucks a month. When did you realize that this was maybe not for your average rock magazine reader, but that the institutions and researchers and writers of the world would be interested in this global trust that you had?

Well, the honest answer is when Harvard University reached out and asked if they could have a quote for a subscription for some or all of the students at Harvard, which was around 2005 or 2006. At that point, it simply hadn't occurred to us, (but we realized that) this was not like the NME online. This was not a magazine. This was a database, and we're going to have to think about it rather differently. I mean, I still think that, to a certain degree, the homepage for Rock's Back Pages reflects my own immersion in magazine journalism, and I hope it kind of speaks to anyone who grew up with or still cares about that. But the reality soon became that if we were going to survive, we were going to have to focus on offering Rock's Backpages as really a research tool. And we could have some fun in a more consumer-facing direction as long as we took care of what it was really about.

Certainly the average music fan, however passionate, at that point, through the naughties, it was clear that they were not… I mean, we're talking about the Napster and post-Napster era where it just seemed like the internet was just a sort of free-for-all and people expected things to be free, and so it was going to be very hard to convert that into revenue. We've always had, just bubbling away, a few hundred individual subscribers. But even they tend to be people who need the resource for a very specific reason, for a limited period of time that they're researching something or making a documentary, or whatever it is that they need to be able to dive deep into pop history for. And some people have subscribed from the very beginning because they were able to get a rolling subscription that was relatively cheap back then. It isn't cheap now, and that reflects the fact that we are more about the group and specifically academic subscriptions.

And the homepage still has stuff that average consumers can partake in, that's like a little taste of what they can get with the full subscription?

Yeah, completely. There is a fair amount of free stuff on Rock's Backpages, and the home page really does reflect that. So every week there's a free feature, and a featured writer where spotlight one of our writers, and there are a good number of pieces for all the major acts that are free. So with any major act… say, there's a hundred pieces about Led Zeppelin, then there are three or four that are free. So you can dip your toes in the water in that way.

And there has to be a strong curatorial aspect in terms of what you do and don't have on the site? Because I'm sure writers come to you and say, “Here's all 5,000 of my pieces. Please take them all.” But your goal is not just to be a dump for everything ever written about rock 'n' roll.

Yeah, there's a decided curatorial element. On the other hand, I'm interested in providing information and data that may be useful. It doesn't have to be deathless prose. So it's not about narrowing it down to the best 30 writers, because there's useful stuff even in some pretty amateurish fanzine interviews. To me, it's really about trying to identity areas that where we can try to get a bit more up-to-date, trying to get more hip-hop writing, more EDM, and so forth. We've probably got enough Grand Funk Railroad pieces. It's about trying constantly to plug gaps, to add more articles about this fairly obscure cult band from Tulsa or whatever it might be, to kind of keep replenishing the thing. If you have a choice between adding a piece about Grand Funk Railroad or a piece about a slightly more interesting band that actually had something to say in interviews, you might opt for the latter. Sorry to single out Grand Funk! I'm no expert on them.

But we just lost one of the great British metal writers, Pete Makowsky. I was never a metal head, but I remember reading Pete's stuff in Sounds in the '70s. So to me, it's important to have he new wave of British heavy metal, which I think was a very I think important and pretty cool moment in British pop music culture. In terms of what we have each week and how we present it on the homepage, we want it to kind of reflect the diversity and depth of what's in the archives. Hopefully it's telling people, there's a lot of unusual stuff in here; this isn't just pieces about Bob Dylan and the Beatles and David Bowie.

Who are some of the more famous or renowned writers that you have on the site that are represented well?

We have Lester Bangs on-site, thanks to discussions that we had with John Morthland and Billy Altman. We have Nick Kent on the site, who's probably the most famous British rock writer. Veterans of the NME… Jon Savage, Simon Reynolds… We have a good number of female writers and that includes Mary Harron and Carol Cooper. I would say it's really evenly divided between American writers and U.K. writers, with some Australian writers and some translated writers from other parts of the world. I lived and worked in America as Mojo's correspondent for a bit, so when we started thinking about Rock's Backpages, it was a help to me that I had befriended quite a lot of American writers, so we reached out to them fairly early on. And we've got now I think over 800 writers across most genres and eras. We have Greg Shaw, Lenny Kaye, Nick Tosches and a lot of the great writers from that early era. Before he died, I managed to make contact with Paul Williams, and that's the beginning of rock 'n' roll writing, Crawdaddy (magazine). We keep adding writers. Quite a lot come to us. We don't always say yes, but we try to be welcoming.

How many pieces overall do you have on the site?

We have a little over 45,000 articles now and are hoping to get to 50,000 fairly soon. This is not industrial farming. This is curated, handmade content. We commit to adding at least 50 pieces a week, from the early '60s to the present day; that's what we commit to doing to our academic subscribers and group subscribers. It tends to be a mixture of long interviews and short reviews. But that's what we can manage with the small team we have, which is four of us who work full-time and two or three who work part-time. It's not like we ever thought, “Well, we could just digitize the entire run of this publication and then just funnel it all into RBP.” It's quite labor-intensive. Everything has to be digitized and proof-read. I think it's good that we take that care with it. Otherwise what happens is … [A company with access to] NME or Melody Maker and others created a database, and it was just done in such a rushed and inept way. Literally the scan would appear in the database and you couldn't even read what was in the margins because they'd just literally pressed down on the page and photographed it. It was nonsense that was no use to anybody. And the writers and photographers particularly were enraged; they'd never been consulted. It was a spectacular cock-up, as we would say here (in England).

Earlier, you said that even though you want to include genres and artists that go up to the present day, there was a peak period for rock journalism. And this maybe speaks to discussions and arguments some of us have all the time. Do we have to pretend that all eras have equal amounts of good and mediocre stuff? Or is it acceptable to acknowledge that, while there is always great stuff happening, there are golden eras? You suggest that hundreds of years down the line, people may take more of an interest in what was happening in the '60s, '70s and '80s, and that isn't just our contemporary bias, but one that may exist in history, where maybe future generations won't have their attention rapt with what happened in, like, 2011 or 2015.

Yeah. I mean, our next podcast guest is Lenny Kaye, and I'm reading his new book, “Lightning Striking.” It's a really exciting read because it identifies these key moments of change, of sort of just ripping up the rule books. I mean, it starts with Alan Freed in Cleveland; it goes on to Sam Phillips and Elvis in Memphis. I mean, these are all in a sense Mojo-esque tropes, but he writes about them, interestingly, in the present tense. And reading them is like sort of being there at these explosive moments. And it just makes you realize how unprecedented those moments were. I mean, I'm only a little way in, but… The contents of the jar have settled a bit, when you've been writing about music as long as we have. And this book kind of shakes up the jar a bit, and it makes it all very exciting again, and it makes you realize how unlikely some of those key moments and key places with key personnel were and how explosive they were, and how they changed the way people experience music and culture and society.

So you also do also do some original interviews yourself, as podcasts.

We just had a John Cale interview on Todd Haynes' Velvet Underground documentary. And with Lenny Kaye, as a writer, as a musician and as a human being, he seems to me to be one of the great people in American pop music history. And the homepage will feature a Patti Smith audio interview from 1978, where she's talking quite a lot about Lenny… For me, the opportunity to digitize a Patti Smith interview from an obscure magazine called Carry Out, that gets my juices going.

You said at the beginning that you feel like a certain kind of rock journalism has ended, or at least waned. What's different now, besides just the music being covered?

To me, what RPG is about and all great music journalism is about is about providing context, is putting meat on the bone. It's not just consuming digital sound files. It's just trying to kind of retain what I experienced growing up when I discovered the music press and what a gateway that was into membership of this sort of tribe — this feeling of being connected to like-minded souls who cared about music and reading these guys once a week in the weekly papers and just finding it so thrilling. And starting to trust certain writers, their tastes, and going out and buying albums based on Nick Kent reviewing them or Lester Bangs raving about them. To me, what's been lost in a sense with the decline of music journalism as we knew it is a matter of sadness. And it probably is for you too. I think we have lost something important there. It's not just nostalgic and sentimental to say that. I feel we're in a world now where somehow consuming music and other artforms has become rather jaded. There's just less excitement. It's like, “Meh… a.”

I mean, this is obvious — everybody's said this stuff before — but I still feel it to be true at some level: Because everything's so accessible, the flavor doesn't last very long on the tongue, and you quickly move on something else. And we're all like, “Okay, all right, what's next? What's the next big thing? Or the next not-even-very-big thing? Do we care that much anymore?” You know, we don't have to work very hard as consumers of music and culture. And to me, part of the magic of it was that you had to hunt things down. You had to hunt records down, and you had to even hunt music magazines down. And it felt precious.

And now, I'm not quite sure, really. I read stuff online. I still think there are writers out there who articulate things way better than I ever could, and they enhance my experience. And I hope that won't ever go away. I don't think it will. I hope people will always want to read about this artform. And if they don't want to read about it in the present, they can always come back to Rock's Backpages [laughs] and see how it was done in 1973 or 1964.

back to Press Room